Albert Mason's: The Suffocating Superego

- drjessefister

- Jan 8, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 16, 2023

Psychoanalysis offers an alternative form of treatment to medication for mental health issues, including severe forms of pathology like psychosis. In this post, I examine Albert Mason’s approach to claustrophobic anxiety manifesting as panic attacks, allergies, and asthma. Using Freud’s topographical model of the unconscious, Mason (1981) hypothesized that excessive moralism, alongside invasive religious indoctrination, leads to the body feeling constricted by overly concretized beliefs about an omniscient, omnipresent God who sees all, knows all, and judges all. This manifests as various forms of somatic disorders affecting aspiration.

To understand Mason’s views on the superego, it helps to imagine the point in human history when we developed the capacity to contemplate death. The upright stance, enlarged brain, and the development of language enabled the development of moral consciousness, not unlike the story of Adam and Eve eating from the tree of life in the metaphorical Garden of Eden. Moralism occurred as the result of intense anxiety created by the awareness of death. To get away from the body which dies, people attempted to live a symbolic and abstract life. The ‘spiritual’ aspects of the person result from the split from body consciousness, which Freud called the ego (“the ego is first and foremost, a body ego”). The result is culture in all its forms as an escape from death, but especially religion. Death is too horrifying to imagine; our best defenses against this terror are building self-esteem and establishing worldview.[1]

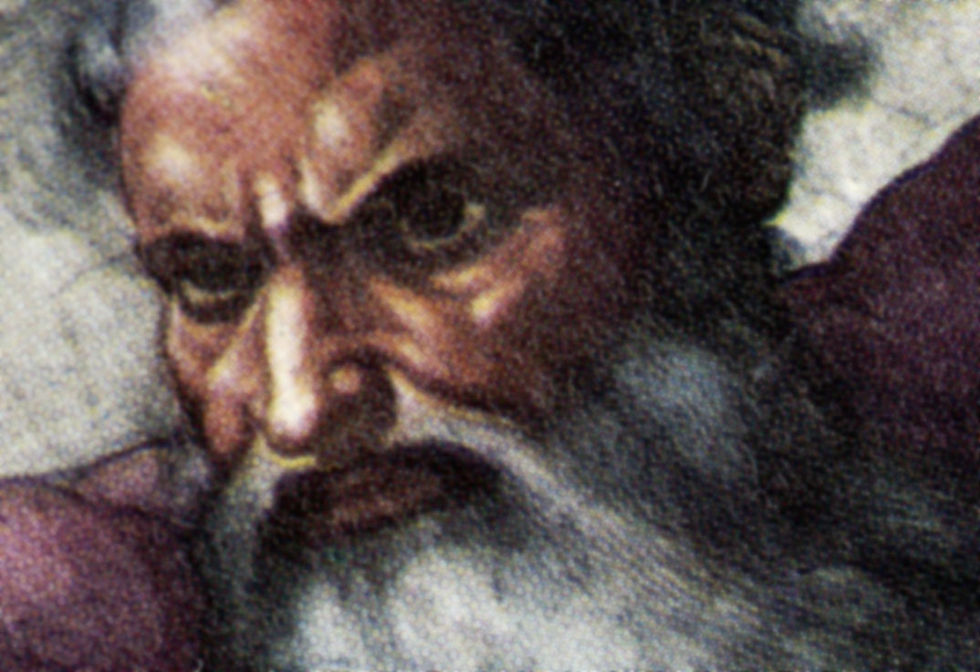

The superego derives from the influence of authority in early childhood. The laws, traditions, punishments, and coercion of parents and social authority become internalized so that the child knows how to successfully navigate the world. In other words, authority becomes a part of oneself. This then gets mixed with infantile fantasies about the world to form a conglomerate called a ‘conscience’. Moses was on to something in the Pentateuch: the awareness of death, the shame of the body, and morality were a simultaneous event in human history, as in adolescent psychogenesis. This conglomerate of internalized authority and infantile fantasies takes on mythic proportions when projected into the universe as the child’s phantasy[2] of ‘God’.

As often happens, the child’s aggressiveness, anger, temper, and rage are condemned by external authority. These are natural emotions that had survival value in prehistoric times but do not lend to modern social life. These feelings must be dealt with. Aside from other defensive maneuvers, one of the most useful ways to deal with one’s internal aggression is to project it one’s phantasies about the person of God. These feelings go well there, because God has a history of violence, anger, vindictiveness, and destruction.

In my clinical practice as a psychologist trainee, I find that people’s anger is often sublimated into excessive moralism. The spiritual or moral side of a person helps them contain their violence, arrogance, judgement, and sadism. Our work in therapy is often to help normalize some of these feelings and find better methods of dealing with them so that they do not turn into masochism. Internalized sadism becomes masochism when violence is turned against the self.

The reason the child projects these emotions outward through phantasy is because they are too volatile and overwhelming to be contained. However, they don’t stay away forever. It takes great energy to pretend that one’s unwanted emotions live somewhere else (e.g., God). They return with a vengeance. Because the wish is to keep it away, these feelings return as forms of persecutory anxiety. The individual feels persecuted by something outside of themselves. This is the same process that occurs in schizophrenia when someone believes aliens, or the CIA, are out to get them.

This phenomenon repeats in large scale in society during conflicts between law enforcement and authority against protestors, revolutions, and other forms of demonstration. When the superego becomes too controlling and persecutory, the people revolt. This happens at an internal scale when internalized authority becomes punitive and overbearing.

Setting aside the ontological reality of ‘God’ for the moment, people project their own expectations onto God. This is not a conscious process. All internalized authority and the latent infantile phantasies about authority are projected into God, meaning that they form one’s expectations about what or who God is and how God acts. When this happens, God can become quite terrifying and overwhelming. The psychic ‘structure’ of these phantasies, emotions, and their dynamics comprises what Freud meant by psychodynamic conglomerate he called the super-ego.

Drugs may be used to dull the excesses of such a punitive super-ego. The other way to placate these persecutory feelings is to project them into outer space and onto the God of the Old Testament. This allows a person to placate their own internal oppression through worship and obedient acts. Religious conversion offers hope of reconciliation and internal peace and stability. Mason described the excessive super-ego as follows:

Omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. The common factor is the word “omni” meaning “all,” thus: all-powerful, all-knowing, all-present. This super-ego quality creates a sensation in the mind of being watched by eyes from which nothing can escape. These eyes are cruel, penetrating, inhuman and untiring. They record without mercy, pity, or compassion. They follow relentlessly and judge remorselessly. No escape is possible for there is no place to shelter. Their memory is infinite and their threat is nameless. The punishment when it comes will be swift, poisonous and ruthless. An important effect of the omnipotent super-ego is the production of feelings of hopelessness which can result in either suicide or psychosis. (Mason, 1981, p. 143)

The super-ego can become tyrannical, invasive, and inescapable, manifesting as a monster or murderer in a bad dream from which one cannot escape. Resistance is futile. It sees all, smells all, and can read thoughts. It surrounds one on all sides. It is crushing and suffocating, creating “acute claustrophobia of the mind” (Mason, 1981, p. 143).

The threat is real. Should the dominating super-ego overtake the ego, fragmentation of the mind will occur, leading to infantile states of disintegration. The body will be threatened with death from within and without, and react as though it were being eaten, choked, or suffocated. The psychosomatic result is asphyxiation in all its forms: panic attacks in acute moments or chronic asthma and allergies where the threat is milder but more relentless.

Phantasies about the all-knowing internal being who judges and condemns every thought, feeling, impulse, and desire becomes invasive and pervasive, as if one were being sexually penetrated. There is nowhere to hide, rest, or breath. It constricts the individual from every side. It is everywhere, the “invasive voyeurist”.

It is this feeling of having no freedom, no exit, no escape, that simulates the feeling of being unable to breathe, the mental equivalent of which, like all sensations of respiratory obstruction produces a violent panic, internal rupture and explosion-the psychotic break. (Mason, 1981, p. 147)

Asthma, claustrophobia, allergies, worship, and forms of paranoia share roots in the same pathological organization of the mind. The individual feels trapped by a tyrannical internal organization from which it cannot flee and reacts as if these persecutions were real. In other words, the phantasies are taken concretely so that the organism of the body fears it were under real threat. The body moves into survival mode. It believes it will die.

To treat such symptoms requires analyzing the unconscious, pre-linguistic structures of the mind through inference and association. Said simply, the best course of treatment is psychodynamic form of therapy, especially psychoanalysis. Cognitive and behavioral approaches cannot get past conscious beliefs into unconscious phantasies where such psychic structures reside. These are deep issues which must be addressed carefully by a mental health professional due to the risk of psychotic fragmentation, suicide, ideological radicalization, or dangerous enactments.

References

Mason, A. (1981). The suffocating super-ego: Psychotic break and claustrophobia. In J. Grotstein, Do I dare disturb the universe? A memorial to W. R. Bion. Karnac Classics.

Comments